The display matrices I had purchased in the recent Anderson auction were heavy enough that it would have cost several hundred dollars to ship them. Instead I took a couple of days to drive to Terra Alta, WV, to visit Rich Hopkins and pick up the mats.

Rich and I cleaned up his storage shed a bit. We both scavenged caster parts that seemed worth keeping, but many of the parts that were considered unlikely to be needed as spares were junked. The general criteria were whether they were parts that wear out, get misplaced, or break easily. Parts in new condition were more likely to be kept, as were parts known to be needed by someone. Rich generously let me take many cases of composition mats that were duplicates of ones he already had, along with some seized but likely repairable Monotype moulds. Once the remaining stuff was sorted and stacked we had reclaimed two skids of floor space.

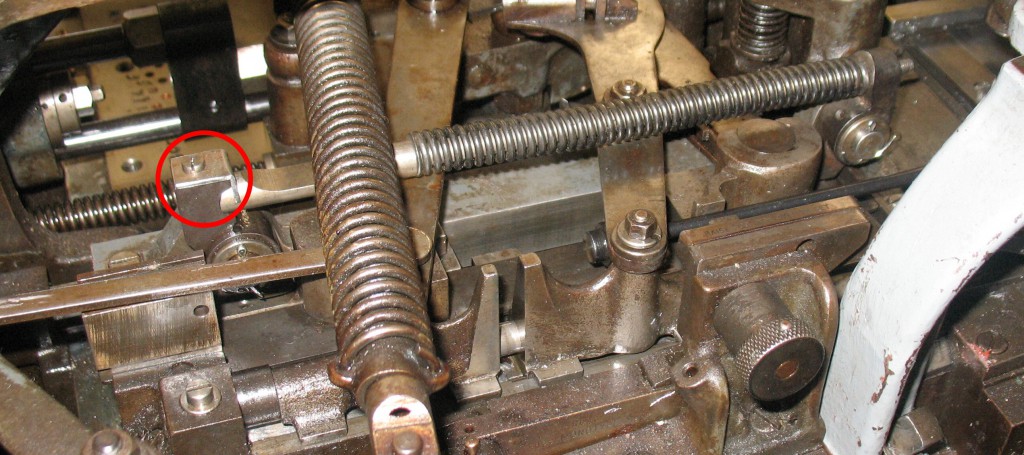

The day I was there, Rich was trying to get some 16-point composition casting done. This uses double-height mats throughout the matcase. We brainstormed a bit to determine what would improve the cast type. Tearing down the mould and cleaning it helped with some of the problems (a lot of flash, and high quads that should have been low quads). The nozzle was also incorrect for the mould, as its tip was sticking up through the mould’s oversize nozzle hole and being struck by the crossblock as the eject cycle started.

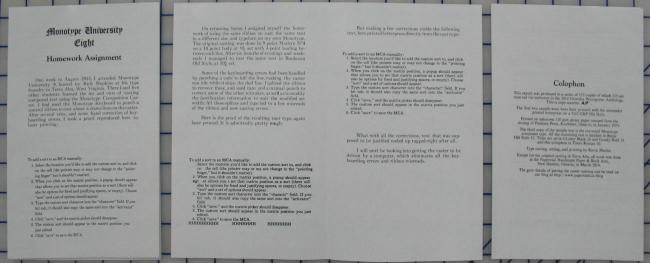

I also brought with me a part for one of his casters. When I was there for Monotype U, I had noticed a makeshift metal strap was being used to retain the end of the spring rod on the front buffer. I had already made a proper retainer for my caster a few years ago, so I made one for his machine as well.

I also brought with me a part for one of his casters. When I was there for Monotype U, I had noticed a makeshift metal strap was being used to retain the end of the spring rod on the front buffer. I had already made a proper retainer for my caster a few years ago, so I made one for his machine as well.

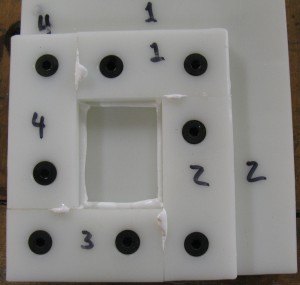

Although I had found the correct screw in my spares to use on my caster, I couldn’t find another for Rich’s machine so I made one. The thread size is almost #8NF36 but the diameter is about a hundredth of an inch less so I had to cut the thread on my lathe.

The retainer on the left is the one on my caster, the one on the right and the screw below it are the parts I made for Rich.

I will also be making for him several of the pin that guides the rear end of the galley fence. This pin apparently breaks quite easily because he has 4 spare fences with broken pins, and the two fences installed on his casters have makeshift pins that flop around a lot. We broke one at Monotype U last summer, due to the mat case not being properly hooked onto the slide behind the bridge. When the caster called for column A on the matcase, it came forward too far and hit the end of the fence, snapping off the pin. I hope to have these ready for the ATF conference in Salem NH this August.