The pump head on my Monotype Composition caster is now back together, except for the pump springs and related parts, which I have to replace with home-made ones to accommodate the pump latch mechanism.

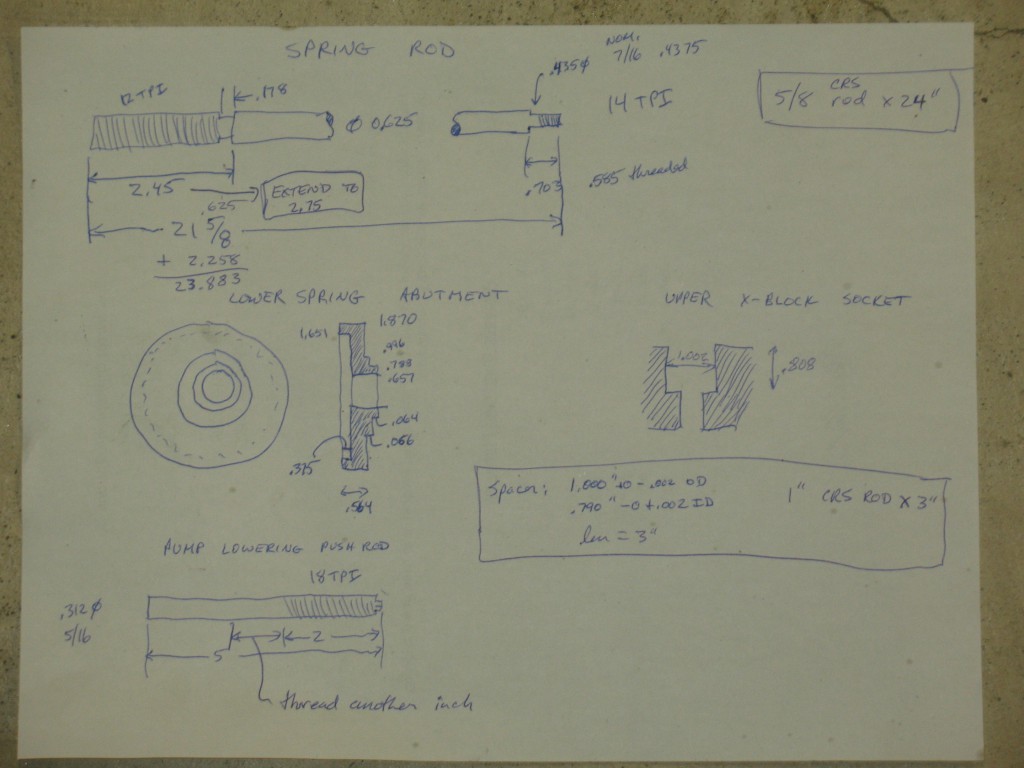

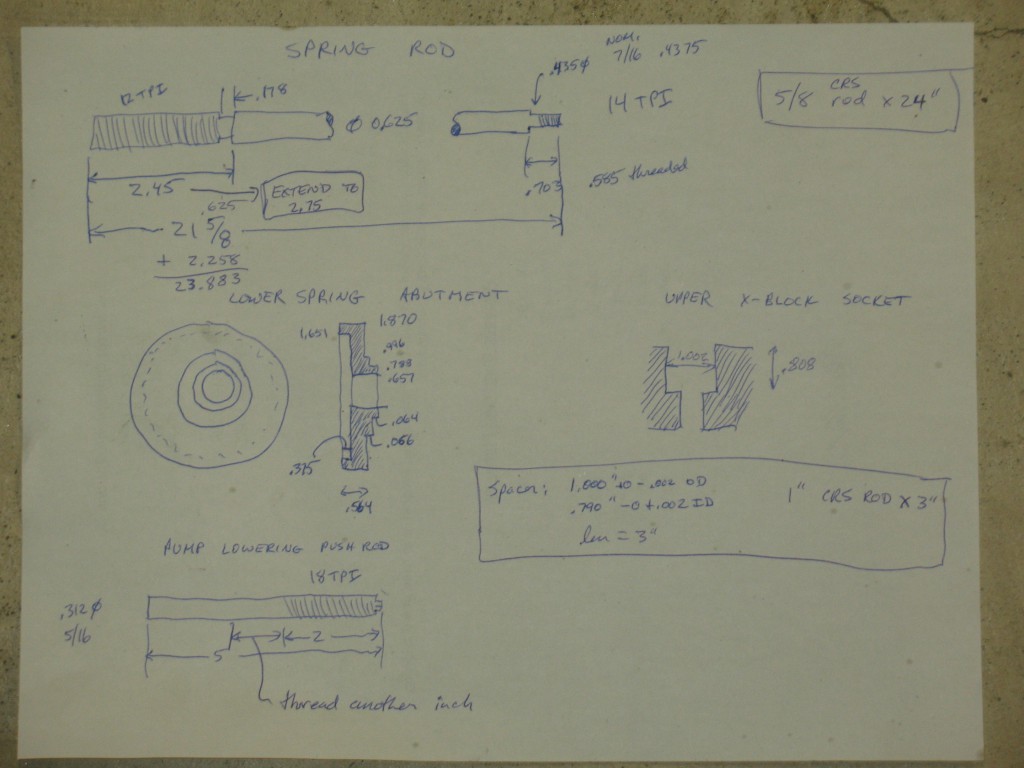

The parts to be made or modified are quite simple, so this is the “drawing” I am working from:

This is the drawing, such as it is, that I am working from. It shows (top) an extended-length pump spring rod c20H1, (left) the existing lower spring abutment a20H12, (right) the socket in the upper crosshead a19H3, (bottom) modifications to my home-made a19H5, and (lower right) dimensions for a new piston rod sleeve b20H7.

As it turns out, the thread pitch on the upper end of the spring rod is 11TPI not 12 as shown on the drawing. Modifying the crosshead stud a19H5 was the easiest and done first: I just had to run the appropriate threading die another inch up the rod.

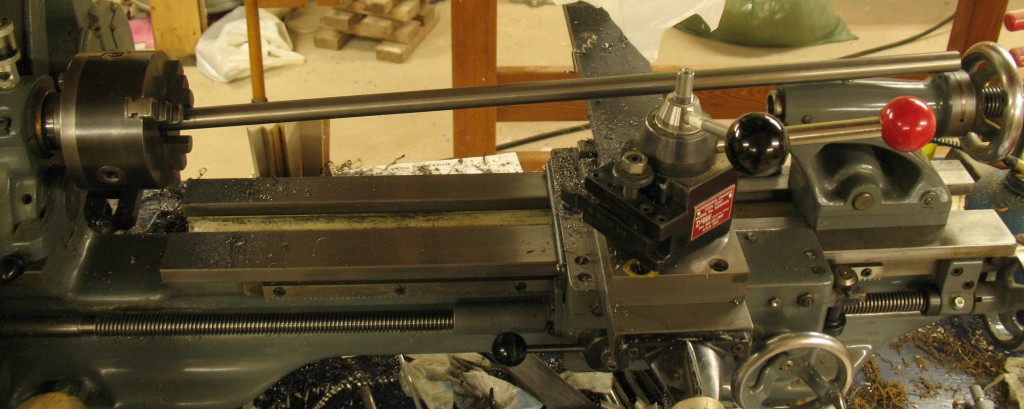

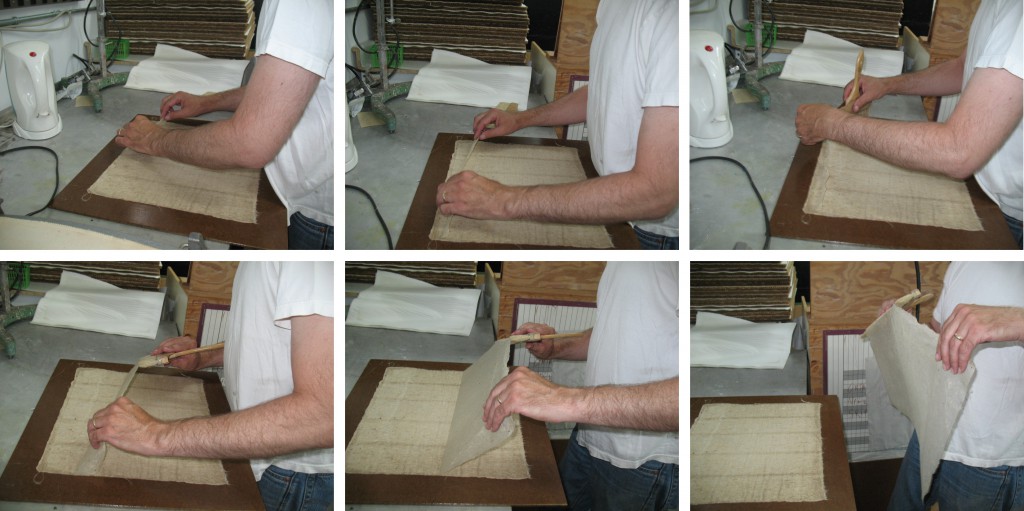

The piston rod sleeve was the next to make. Starting with a length of 1″ diameter hot-rolled round stock (I did not have any cold-rolled), I faced one end, drilled a ¾” hole down the center, and bored partway in to match the diameter of the step in the lower spring abutment.

This shows the sleeve with one end bored out. The boring tool is a bit out of focus. This diameter actually only has to be bored a little over 1/16″ but I gave it extra depth because it looks better.

I then reversed the sleeve in the lathe, bored the other end (so it could be installed either way up) and faced it to the correct length. Because I used hot-rolled stock, the outside diameter was covered with mill scale which I removed by filing it off, although there is a bit of scale still showing in some pock marks. I would not have had to do this had I started with cold-rolled stock. All the sharp edges and burrs were removed, giving the finished part, which is a nice snug fit with the spring abutment.

The last part, the longer spring rod, is another story and another post…

The pulp is a pale cream colour (the photo also contains a sheet of white paper for reference) with occasional small stained spots from its use as drying blotters, and the sheets are 26×36″ which is just slightly smaller than our drying system (27×36″).

The pulp is a pale cream colour (the photo also contains a sheet of white paper for reference) with occasional small stained spots from its use as drying blotters, and the sheets are 26×36″ which is just slightly smaller than our drying system (27×36″).